The Pâté, Jean-Baptiste Oudry, 1738The following is my paraphrased summary through chapter one of thesis: Blanchette, Jean-Francois (Ph.D.: Anthropology, 1979, Brown University) Title: The role of artifacts in the study of foodways in New France, 1720-1760 : two case studies based on the analysis of ceramic artifacts.

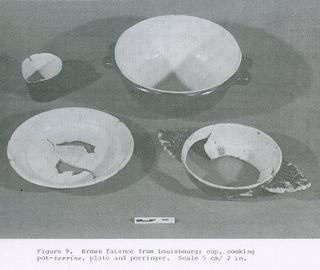

The Pâté, Jean-Baptiste Oudry, 1738The following is my paraphrased summary through chapter one of thesis: Blanchette, Jean-Francois (Ph.D.: Anthropology, 1979, Brown University) Title: The role of artifacts in the study of foodways in New France, 1720-1760 : two case studies based on the analysis of ceramic artifacts.The study of brown faïence is a well-defined ethnic type, being manufactured only in France. Its presence or absence on any site occupied by the French during the French regime should reveal preferences for culinary equipment and, undoubtedly, particular alimentary orientations related to status. In fact, the beginning of the 18thC was a period when the ceramic arts, particularly faïence, flourished. At this time Louis XIV ordered the silver and gold table services to be sent to the mint to pay for the excessive expenses incurred by foreign wars. These table services were replaced by faïence.

Although brown faïence was invented during a period of liberalism in the industry, the limited supply of wood fuel for kilns caused stipulations that production must be for either white or brown faïence. The exclusive production of brown faïence, or brown with white interior, made it possible for numerous Rouen factories to exist until well after 1786, even though cheaper, prettier English pottery which had the appeal of a foreign product was preferred, brown faïence continued to persist as both kitchen- and tableware.

For many centuries, meals had been composed of either potages or stews, made thick by the addition of bread. Meals, in which meats, spices, and other rare products could be found, were for well-to-do people—the common people were eating plain and frugal fare, which seldom included meats, except for special social or religious activities. Meals of the lower class tended to remain the same, but meals of the upper class went through a revolutionary change as evidenced by their cookbooks (Bonnefons 1651; L.S.R. 1674; La Varenne 1699; Liger 1700, 1755; La Chapelle 1735; Lemery 1745; Marin 1775). The change in haute cuisine was that of cooking food slowly, in its own juices: meats were cooked individually, spices selected and vegetables prepared separately, to say nothing of the diversity of pastries and desserts. Ceramic vessels became the preference for slow cooking, metallic ones when a fiercer fire was needed. The variety of brown faïence vessels corresponds to the needs of the new cuisine. Marin summarizes numerous details about the ways of preparing meals, the quantities for necessary ingredients, cooking time, necessary vessels for preparation—glazed earthenware pots, terrines,

huguenotes

huguenotes (tripod cooking pot), earthenware or copper pans and kettles, water kettles, silver and faïence platters. In fact, the first book addressing itself to the bourgeoisie in addition to the nobility and the clergy was Menon’s

La cuisinière bourgeoise published in 1746.

It was toward a refinement and a tasting of individual food that the kitchen of the French nobility was aiming. A significant element of Bonnefons’

Les délices de la campagne concerned the cooking and preparation of root vegetables, such as carrots, parsnips, white salsify, beets, rapes, turnips and Jerusalem artichokes. Usually considered food in times of famine and bad harvests, Bonnefons brought these foods to the table of the leisure class. Sugar now played an important role and was used for many things, including decoration. Sauce was thickened with flour and heat rather than with soddened bread. Three elements of this cuisine are: wet dishes—stews, potages and sauces; dry dishes—cooking in undercrusts, the use of waxed paper for cooking, the practice of multiple cooking using two different techniques; and liquids—coffee, tea and chocolate.

Wet dishes include creams, eggs, and other side dishes which were partially or totally prepared in hollow platters or on dishes over a gentle fire. Cooking was slow and meat was often left to cook on a gentle fire to extract its juice. Braising was another technique.

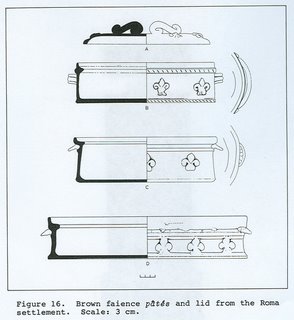

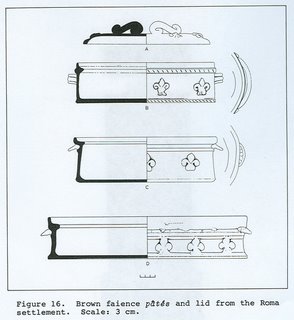

Pâtés were dry dishes, meats cooked in undercrusts which were either puffed pastries made of wheat flour for fine dishes, or a combination (

bise) of wheat and rye flour for large cuts of meat. These undercrusts were sometimes decorated with fleurs-de-lis made of paste (Liger 1755). No vessel was needed to cook the pâté because the solid crust replaced it. The pâtés could also be cooked directly on the sole, (oven floor) or on a piece of waxed paper in the oven, as was the case for meat preparations that held their shape. This method of cooking was expensive because the paste hardens during cooking and was later discarded. Numerous meats, fishes and other dishes were often cooked twice. They were first cooked on a spit or cooked slowly in a pan or platter. The second time they were arranged on a serving platter of silver or faïence and covered with grated cheese, cream or other decorations and set in the oven or on weak embers, thus producing a glaze. This method of cooking was a new refinement not found in recipe books from the preceding century.

Brown faïence dishes, called pâtés after the food, made it possible to cook these dishes without undercrusts which were expensive for those who did not have large quantities of grains for flour in storage. The food was put in pottery pâtés and placed in a

bain-marie so that the water in the

bain-marie would replace the humidity otherwise supplied by the undercrust containing the pâté.

Blanchette suggests using brown faïence pâtés to eliminate the need for undercrusts was very economical and the pâtés were decorated with fleurs-de-lis, like the undercrusts. The tops of the faïence pâtés were often decorated with rabbits and feathered game to suggest the type of meat used.

Liquids, like wine, were often suggested to prepare meats and fishes. Wine was also used for the preparation of hot and cold drinks. Tea, coffee and chocolate were not mentioned in recipe books before the 18thC. Liger (1755) specifies that coffee grains are roasted in glazed earthenware vessels so that they won’t burn and all their taste is preserved. He also says that water for tea boils in a

cafétière (coffeepot).

In fact, authors of cookbooks never use the term

théière (teapot) in any of the books analyzed, although the teapot shape is found archaeologically in 18thC sites and mentioned in documents at mid-century. The pitcher, coffeepot, chocolate pot, teapot, small pouring pot, globular cup and straight-sided cups are all brown faïence shapes related to beverages and relative consumption seems to correspond to relative occurrence in New France archaeological sites.

Development of the new cuisine in France coincided with the development of brown faïence, and the shapes of this ceramic type correspond well to the preparation-service-consumption of the foods previously noted. Thus it would seem that brown faïence was manufactured for the preparation and service of dishes found in the new recipe books, since the diverse specialized shapes correspond so well to the foods. In effect, the development of foodways follows the general progress of French society as seen in standards of living, demography, the bourgeoisie and colonial commercial activity. This general frame of reference should be kept in mind in understanding the role and position of brown faïence in culinary innovations of the 18thC.

The pitcher is a pot with a slight pouring lid and a handle. Its neck is long, straight and vertical; its body is globular.

The pitcher is a pot with a slight pouring lid and a handle. Its neck is long, straight and vertical; its body is globular. The coffeepot is a pouring pot in which the walls are uniform and slanted toward the bottom and the handle is horizontal and straight “used for heating all type of beverages” (Encyclopédie 1765: Fayancerie, PL I: 4) The author does not make a distinction between the coffeepot,

The coffeepot is a pouring pot in which the walls are uniform and slanted toward the bottom and the handle is horizontal and straight “used for heating all type of beverages” (Encyclopédie 1765: Fayancerie, PL I: 4) The author does not make a distinction between the coffeepot,

and the coquemart [Fig. 6] (see text of the encyclopedia). Furetière 1970, however, says that the “coffee pot” is a “small coquemart-shaped vessel in which coffee is prepared.”

and the coquemart [Fig. 6] (see text of the encyclopedia). Furetière 1970, however, says that the “coffee pot” is a “small coquemart-shaped vessel in which coffee is prepared.”  It has a handle, and the spout is separate from the pot’s opening. The teapot usually stands lower than other pots of normal size. In the Recueil de plances (1765 in Encyclopédie: Fayancerie I:7), it states “A tea pot to be used with a tray (name given to a platter carrying a number of coffee cups), usually made to contain coffee.”

It has a handle, and the spout is separate from the pot’s opening. The teapot usually stands lower than other pots of normal size. In the Recueil de plances (1765 in Encyclopédie: Fayancerie I:7), it states “A tea pot to be used with a tray (name given to a platter carrying a number of coffee cups), usually made to contain coffee.”

This text is probably another indication that tea was not widely used.

This text is probably another indication that tea was not widely used.